The truth about your pace, those walking breaks, and your knees—lots about your knees.

Collage: Self ; Source images: AN Studio/Ivan Pantic/Getty Images

All products featured on Self are independently selected by our editors. However, we may receive compensation from retailers and/or from purchases of products through these links.

In my 20 years of running and almost as many years of writing about it, I’ve encountered a load of misperceptions about the sport. These myths aren’t just annoying—my knees are perfectly fine, thankyouverymuch—they can seriously stand in the way of progress or even keep people from trying running in the first place.

There are just so, so many “truths” about running that are anything but. And recognizing which adages are nothing but bunk is the first step in making sure you don’t get taken in by them. So I’m making it easy for you: Below, 10 running myths top coaches see new runners mistakenly buy into—and the facts that could open the door to a healthy, long-term relationship with the sport instead.

1. Running will wreck your knees.

If there’s one myth that just won’t die, it’s this one. Most runners have heard that they’re inevitably setting themselves up for a future knee replacement—or years hobbling around doing just everyday activities—by repeatedly pounding the pavement.

But the truth is that human bodies aren’t machines with parts that simply wear out with use. Rather, they’re dynamic systems that respond to appropriate levels of stress by adapting, certified running coach Neely Spence Gracey, owner of Get Running Coaching in Boulder and my coauthor on the book Breakthrough Women’s Running: Dream Big and Train Smart, tells SELF.

Research bears this out—and with a surprising twist. Studies suggest folks who run regularly actually have a lower risk of osteoarthritis and similar conditions over the long term. That could be because running strengthens the muscles surrounding your knees and also stimulates positive changes in the cartilage that protects and cushions the joint.

Yes, some runners do get short-term knee problems, including patellofemoral syndrome or runner’s knee, and others have specific joint conditions that make running more challenging, if not impossible. But for most people, a smart training program that builds over time, incorporates strength training, and allows ample rest will result in better joint health, not worse, Tia Pettygrue, a certified running coach in Tampa, Florida, tells SELF.

2. Running needs to be fast—and then get even faster.

People who are new to the sport—or haven’t run for a while—often begin by making each run a nearly all-out effort, Gracey says. “Then, they think they need to improve every time they go out the door,” Tammy Whyte, an RRCA-certified running coach in Chicago, tells SELF.

This approach poses a double whammy: It makes each run much, much harder than it needs to be. And, if you’re constantly in pain or dreading your next outing, it’s far more difficult to build consistency, which is the only thing that will ever make running feel any easier. “That’s when people get injured; they get burned out,” Gracey says. “They’re like, ‘Oh, running sucks. I hate running.’ But it’s because they progress too quickly.”

The far better strategy, coaches say, is to ease in slowly and build a sustainable habit. Start with walking and then begin adding in running intervals. (That’s exactly what we’re doing in SELF’s Learn to Love Running Program!) Keep the effort level as easy as possible at first—no more than a 3 or 4 on a scale of 1 to 10, Pettygrue recommends.

In fact, even once you’re experienced, most of your miles should fit right there on the scale too, Whyte says. (That’s what you often hear called “easy miles.”) More relaxed efforts build your cardiovascular base. Your heart becomes stronger, so it can pump more blood through your hard-working body. New capillaries sprout to shuttle that blood to your muscles, which also grow tiny energy factories called mitochondria to power your efforts.

Once you’ve been running consistently for a few months, you can add on interval workouts or tempo runs, which incorporate faster running to further boost your fitness and build speed. But a little goes a long way—Whyte assigns her advanced runners only one to two such sessions per week.

3. You should run every day.

All those changes to your cardiovascular system occur in response to the challenge running places on your body. Each run also stimulates modifications that make your tendons, muscles, and bones stronger and more resilient, so you can run even longer the next time.

Applying the stresses of training at the right dose takes consistency, but it’s actually in the downtime between runs that all those beneficial adaptations occur. When you’re first starting out, it’s a good idea to take at least a full rest day in between each of your runs. (Try not to stretch it to more than three days in a row without a run, though, Gracey recommends.)

As you progress in your training, you might run more often, but striking the balance of hard work and ample recovery still matters. About 90% of the runners Gracey coaches, including those running speedy marathons, take at least one rest day weekly, she says.

4. If you stop to walk, you’re not a runner.

Like we mentioned, SELF’s Learn to Love Running program builds you up from a walk to a run/walk to a continuous run. But even before you get to its ultimate goal—running 30 minutes continuously—you’re undeniably a runner, Pettygrue says.

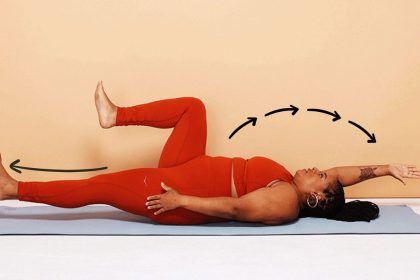

In fact, she—and many other experienced runners—continue to use walk breaks as they build up their distances. The idea is to strategically place lower-intensity intervals throughout your run, so you keep your mind engaged and prevent fatigue. Many people, including Pettygrue and some of her athletes, find they actually run faster this way.

Pettygrue follows the Galloway method, developed by Olympian Jeff Galloway, who suggests determining the duration of your running and walking breaks based on pace. For example, Pettygrue’s pace is usually around an 8- or 9-minute mile, and she normally runs 2 minutes, then walks 30 seconds. (If your pace is a little slower—say, around an 11-minute mile—you might run 60 seconds and walk 30 or run 40 seconds and walk 20.)

But regardless of whether you use a formula or simply take a few slower strides when you get gassed, don’t let anyone convince you walking makes you weak. “You choose how you want to do it,” Pettygrue says. “Run-walk does not make you any less of a runner.”

5. Runners never lose their motivation.

Scrolling social media can have you believing runners always feel amped up to get out there and train. Every. Single. Day. “People think that, if they’re not always motivated, there’s something wrong with them,” Whyte says.

The reality is that even the most dedicated athletes sometimes struggle to get out the door. When that happens, they rely on their deeper commitment to their goal, whether that’s achieving a particular time in a race or simply improving their health and well-being.

Regular runners also learn to build systems to support consistency, Whyte says—for example, finding a training partner or a group—and reward themselves for showing up even when they don’t feel like it (say, with new gear or a self-care day).

The good news is that the more time you dedicate to building a habit, the easier it is to ride the ebbs and flows. “Motivation comes when you see progress,” Whyte says. “Sometimes you actually have to do the thing to then get motivated to do the thing, because you see that you’re improving.”

6. Running is a solo sport.

About those running groups—sure, they can feel intimidating to newbies. But these days, there are more of them than ever before, catering to all different levels of runners, Whyte says. Search and ask around, and you’ll likely find one or more that match your fitness level, goals, and personality.

When you do, you might find more than motivation. Yes, running is technically an individual endeavor, but doing it alongside others can forge powerful connections that transcend the sport. You might find a team of people rooting for you, as well as an entirely new friend group. “My husband always says running races is our social life,” Pettygrue says.

7. You need to have a “runner’s body” to run.

Ask most people to picture a runner and chances are they’ll think of someone leanly muscled. “There’s definitely a stereotype,” Pettygrue says. “But runners come in all shapes and sizes.”

What’s more, bodies change over time. While hers has been several different sizes throughout her running journey, it hasn’t prevented her from enjoying the sport or accomplishing goals like running a time fast enough to qualify for the Boston Marathon.

She suggests anyone feeling doubtful about their body should go watch the finish line of a marathon. “You will see every kind of person, and it’s so inspiring to see that you don’t have to look a certain way. You don’t have to weigh a certain anything,” she says. “It’s all about putting one foot first.”

8. You have to race long distances to be a “real” runner.

But just because all those different bodies can run marathons—and influencers seem to post about doing one approximately every other weekend—doesn’t mean you have to do the same if you don’t want to, Gracey points out. “When I first started, I focused on the mile, and that was my main goal,” she says.

Many runners find racing 5Ks—that’s 3.1 miles—offers the perfect balance of an approachable challenge, she says. And to be perfectly honest, you don’t ever have to pin on a bib at all to consider yourself a runner. While races can motivate you to train consistently, provide a fun chance to connect with the running community, and offer an opportunity to step outside your comfort zone, it’s also totally legit to enjoy running for its own sake.

9. I couldn’t ever run that far, anyway.

When Pettygrue reached the 10-mile mark at her first half marathon, she had a thought. If she were running a full marathon, or 26.2 miles, she wouldn’t even be halfway done. At the time, she thought there was no way she could—or would want to—take on the longer distance.

Now, more than 15 years later, she’s finished 12 marathons and more than 170 half marathons. She’s also guided more than a thousand other runners on their goals, as well as mentoring other coaches through the Game Changers program. Her experience illustrates one of the biggest myths about running, she says, which is: “I could never do that!”

As mentioned, you don’t have to run a full marathon or even race at all to be a runner. But knowing the truth about longer distances—that if you want to take them on and you follow a sustainable approach to increasing your mileage over time, you can reach them—can break down barriers to any goal.

10. It’s too late for me to get started.

You don’t have to have an athletic past to get hooked on running now. Gracey mentions an athlete she coaches who didn’t begin running until his late 30s, and now, in his mid-40s, he has a goal of running faster than 2 hours and 50 minutes (that’s a pace of under 6 minutes, 30 seconds per mile—so, speedy!) in all the big-city races that make up the Abbott World Marathon Majors.

Even athletes well into their middle or later years can make running a regular part of their lives, says Whyte, who coaches many athletes in their 50s and 60s. You might want to check in with a medical professional first if you have health problems, especially if they affect your muscles, bones, or joints—and building up may take longer than it would if you were, say, in your 20s.

But in most cases, age isn’t a barrier to getting started, enjoying mental and physical benefits like a better mood and healthier heart, and maybe even discovering a hidden talent. “Running can meet you in so many different phases of life, unlike a lot of other sports,” Gracey says.

Related:

- I Used to Hate Running. Here’s How I Learned to Actually Enjoy It

- 6 Common Habits Podiatrists Say Are Wrecking Your Feet

- What Does ‘Proper’ Running Form Really Look Like?

Get more of SELF’s great fitness content delivered right to your inbox.